The Origins of Shinkendo

History of Swordsmanship

After the battle of Heiji No Ran in 1159, the Heike defeated the Genji clan. The Heike leader, Taira No Kiyomori, assumed the powers of the emperor and initiated a political system, similar to that of the nobles. Due to this change, the Genji revolted. In March of 1185, Minamoto No Yoritomo led the revolution that ultimately was the downfall of the Heike clan. Then, in 1192, he became the first Shogun and established the Kamakura government. This government was made by and for the Samurai, and emphasized a government based upon bujutsu and spirit.

After the battle of Heiji No Ran in 1159, the Heike defeated the Genji clan. The Heike leader, Taira No Kiyomori, assumed the powers of the emperor and initiated a political system, similar to that of the nobles. Due to this change, the Genji revolted. In March of 1185, Minamoto No Yoritomo led the revolution that ultimately was the downfall of the Heike clan. Then, in 1192, he became the first Shogun and established the Kamakura government. This government was made by and for the Samurai, and emphasized a government based upon bujutsu and spirit.

For spiritual study the Kamakura era samurai studied Rinzaishu Zen, which was the religion of choice - both favored and protected by the second shogun, Minamoto no Yoriie as well as the third shogun, Minamoto no Sanetomo. This sect of Zen was popular with all the top level samurai. Its practice consisted of sitting and answering the questions of a monk, and taught one how to understand yourself and achieve enlightenment. Later, the Sotoshu Zen sect developed, which consisted of sitting and allowing the mind to empty, at which state enlightenment could occur. The Sotoshu first became popular in Northern Japan, but eventually spread across the country.

The Sengoku era was a time of battles, and during this time three prominent heroes emerged: Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu. These three men helped to unify the country and it was during this period that the Gekokujo, or revolt, occurred between the lower ranking officials and their superiors in an effort to usurp their rank and power. Even during this time of revolt, strategy and the principle of warfare in bushido were extremely important. Throughout history, some form of bushido has always existed and been revered.

The Edo era began a time of peace, which reigned for 265 years, and the concepts of budo began to change. At that time there existed 200 famous kenjutsu ryu-ha (sword traditions) and more than 3,000 lesser known ryu. Budo was no longer concerned with winning a battle, but geared toward the development of mind and spirit. In budo, the goal was to be strong and effective, and as a by-product of hard training, the mind and spirit would develop naturally. Strength is not to be confused with violence. The goal when practicing is to care for and respect your partner (opponent). If not, you or your partner would suffer the consequences of injury, which would in turn hamper your training.

In 1867, the Tokugawa government had fallen, and warriors' world came to an end. By 1868, the Meiji era brought with it an influx of European civilization and culture. In 1876, the haitorei was issued which banned samurai from wearing swords in public. The sword was no longer the trademark of the samurai. Fewer and fewer people practiced swordsmanship until finally, the art became obsolete and many traditions disappeared completely. This began a period of time when swordsmanship was no longer exclusive to the samurai (bushi) class, and any citizen could learn how to use a sword. Subsequently, this period saw the birth of many seiza-based iaido sword groups. This was indicative of the change from "jutsu" to "do", as bujutsu changed to budo; kenjutsu to kendo; and jujutsu to judo.

After Japan was defeated in World War II, martial arts was banned. The concept of budo changed drastically and was, generally speaking, no longer a combat effective art, but that which was evolving into a more spiritual, non-aggressive art.

The following interview (unedited) was conducted and translated by Sachiko Kunisawa, in response to frequently asked questions....

Nakamura Taizaburo sensei

In the 6th year of the Meiji era (1873), the army established the Rikugun Toyama Gakko (a military school located in Toyama, Tokyo). Among other traditional skills, gunto soho was taught, which was the study of using the army sword. It was an accelerated course to train officers in the effective usage of a Japanese sword in a short period of time. Later, in the 10th year of the Showa era (1925), the techniques were refined to create Toyama ryu. There were only seven simple, but practical basic techniques in the Toyama ryu curriculum. Nakamura Taizaburo sensei was a Nanpo kirikomitai Budo Kyokan, or, instructor of sword attack. After the war ended, he continued to do demonstrations of tameshigiri (test cutting). Unfortunately, Nakamura sensei was chided by the public because the public felt that sword was the only skill he was experienced in.

As peace continued to prevail, many martial artists began to re-examine this modern non-combative budo and questioned its effectiveness. Nakamura sensei was continuing to broadcast on t.v. his test cutting demonstrations and people were starting to take notice. Different styles of kobudo were also introduced and in a demonstration held in Houno enbu (dedicated to the Meiji shrine), a number of instructors throughout Japan came and performed. Although each group claimed a long history and tradition, most of the styles looked the same and it was doubtful that any of the techniques could have actually been used by the samurai in battle.

For whatever reason, some styles added an element of Zen to their techniques and made the movements slow and unlike anything a warrior would practice. Zen is a spiritual study, not a type of budo.

During this time I was uchi-deshi (live in student) at the Yoshinkan Aikido honbu dojo. I attended a budo demonstration, wherein I performed aikido. Mr. Nakamura also did a demonstration. Although he was already in his fifties, he still had power and focus in his cutting and it caught my attention. I wondered how much speed he had in his younger days. At the time, Nakamura sensei brought his own test cutting material and handled the setting up and cleaning up by himself. I thought I would like to study with this man if I had the chance, so I volunteered to assist him.

Since studying any other art while being an uchi-deshi at the Yoshinkan was forbidden, it was not until I left Yoshinkan and entered the Wakakoma that I was able to study with Nakamura sensei. I never missed one of his seminars. Often, there would be other swordsman there practicing iai (seated) techniques. I found it amusing that Nakamura sensei would question them on why anyone would want to sit down with a sword (especially when a traditional samurai would never wear their long sword indoors. it was considered poor etiquette), and none of them would answer. These practitioners were taught these techniques by their instructors and one could guess that someone, at some point in time, changed the art, which is disappointing.

Toyama Ryu Soke

I feel a soke (founder and/or headmaster) certainly has a right to change or modify an art; but often changes are so frequent that the original techniques are unrecognizable. Mr. Nakamura was criticized for doing just that when he began practicing Omori ryu from a standing position, since it had developed as a set of seiza (sitting) techniques.

Several years ago, Victor Figueroa wrote in an iaido newsletter that "Obata's Toyama ryu is not Toyama ryu". To that I can only respond that it is not his fault that he is unaware of the changes in the Toyama ryu kata over the years. I feel it is his instructor's responsibility to disseminate accurate information about the art, and I am not interested in defending my position.

In Japan, when budo is taught, one does not question his instructors. It was considered virtuous and honorable never to question or doubt your instructor. Since new practitioners are novices and cannot recognize a good technique from a bad one, it becomes a tragedy of sorts when a student has a misinformed instructor.

In traditional budo, the art is passed by watching your instructor and mimicking his movements. Techniques are not memorized, but ingrained in the body through hard training, so as to become second nature. Your body should react without thought in a real life-threatening situation. Your senses become sharper and you create variations, to keep the mind and body alert. Training without variation cannot create a dynamic and vital art, but encourages the art to "stagnate", and can allow weak or incorrect technique to be passed on to subsequent generations.

During Nakamura sensei's seminars, I would keep very busy assisting other instructors. I was concerned that these teachers may injure themselves, and indeed many of them struck the floor with their swords, unable to control and stop their swing. Some had such loose grips that the sword actually spun out of their hands. Making a mistake during practice is understandable, that's why its called "practice", but safety should always be the number one priority. Even Mr. Nakamura has injured himself several times with his own sword, which he states in his book. In my opinion, an injury can only be the result of insufficient practice or poor technique.

It is truly a shame, when senior Instructors pretend to know what they are doing or boast about their ability, when they lack even a basic understanding of sword technique. There are people around the world creating their own styles, and ironically these are the same individuals who end up injuring themselves or their students.

Although I was one of the youngest participants in these seminars, many older instructors would ask for advice, which I greatly admired them for. In Japan, there is a saying "Kiku wa ittoki no haji, kikazaru wa issho no haji", which means pretending to understand and not ask for help, results in a lifetime of shame. There is an American adage which is just as appropriate, "Better to ask questions once and be thought a fool once, than never to ask and remain a fool forever".

I really didn't participate in seminars - I usually ended up watching and studying the movements and styles of others; thereby learning what was effective and what was not. More than one teacher came up to me after a seminar, complaining how dull their sword was, to which I responded with a cutting demonstration. The swords were usually very good quality and I was always able to make clean cuts with every sword, and thus discovered that the swords were in fact sharp and that it was an error on behalf of the practitioner.

Tatami Omote

There was a tatami store near my home and I would go and get leftover tatami, which I used for target practice. I used this instead of wara (straw) since straw was hard to come by in the middle of Tokyo. I started using tatami omote sheets (the top layer of a tatami floor board), which I would roll up and soak in water for a short time. This method is very different than the full tatami (floor board) mats that were used for cutting back in the Edo era. Previously swords were "tested" on battlefields, but during times of peace, the bodies of executed criminals were used for sword testing instead. Since there was only four public executions during the Edo period, the executioners found an alternate target to practice with, and had begun cutting tatami floor boards.

The straw and bamboo targets were used to simulate flesh and bone; however, using tatami omote instead of straw I feel gives a firmer, more solid feel to the target. I would never recommend using just any object as a target, and I think it is disgraceful that people use fruit, such as watermelon, in exhibitions. Firstly, a sword is not just a weapon, but also a spiritual symbol of the samurai. Secondly, sugar is very damaging to swords. Why use a sword when a kitchen knife would do? My feeling is that these type of acts more closely resemble street shows, and not martial art exhibitions. I don't recommend cutting hard material either. Why risk damaging a sword? There is no reason to damage a blade this way, especially if it is a historical artifact. Now, sword testers cutting into a hard object to determine the safety and effectiveness of a sword is another thing. On the other side, there are those who insist test cutting is completely unnecessary; but I would ask them, how can one be sure of their technique unless it has been put to the test? I liken it to shooting a gun without bullets; one cannot accurately evaluate their skills without concrete evidence.

As I continued to use tatami omote, it was later incorporated (at my suggestion) for demonstrations of Wakakoma's stage performances, and later for the battodo tournaments (because of the consistency of the targets and the ease of clean up). Soon, tatami omote became the standard in all test cutting competitions and target cutting practice. Contrary to popular belief, tatami omote IS NOT a traditional target, but something that ended up being adopted by the sword community as a result of my own experimentations.

The one thing about tatami omote that is negative is that the cut piece will not tend to stay in place after it has been cut like wara (straw) targets. This looks very dramatic, but tatami omote is heavier and the surface of the cut is too smooth for it to stay in place, unless an exceptionally thin/ wide sword is used, like those popularized in recent Tameshigiri competitions.

Background of Battodo

Gunto soho (Army sword technique) was first developed as a military set of techniques, subsequently the name was changed to Toyama ryu iaido, then finally the Zen Nippon Battodo Renmei. This came about for a number of reasons, including a desire to open test cutting competitions to swordsman other than those in the Toyama ryu. Nakamura sensei wanted to change the name because Toyama ryu was the name given for the Army's style. Nakamura was not particularly high ranking in the military, and there were those who objected to him using the Toyama ryu name for personal gain.

There was much discussion on potential names, and I recalled the old name of swordsmanship, iaibattojutsu. Iai had become iaido, and following that line of thought, I suggested battodo. My suggestion was accepted and I was awarded a lifetime membership into the Zen Nippon Battodo Renmei. Shortly thereafter, the first test cutting tournament was held.

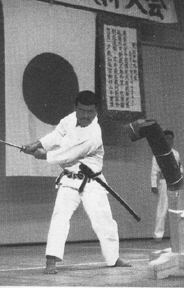

Obata at the 3rd Annual All Japan Battodo Tameshigiri Competition

In the tournament there were over two hundred participants. The competition consisted of kata, emphasizing a dignified execution of techniques and test cutting, where accuracy and quantity of cuts were judged. I ended up winning the battodo tournament for two consecutive years, then went on to win the Ioriken battojutsu competition (which focused on speed and accuracy) for four years in a row.

In the tournament there were over two hundred participants. The competition consisted of kata, emphasizing a dignified execution of techniques and test cutting, where accuracy and quantity of cuts were judged. I ended up winning the battodo tournament for two consecutive years, then went on to win the Ioriken battojutsu competition (which focused on speed and accuracy) for four years in a row.

I received a menkyo kaiden from Ioriken battojutsu, and Nakamura sensei awarded me a Beikoku Battodo Renmei Honbu (USA Battodo Federation Headquarters), a Toyama ryu Battojutsu Beikoku Honbu (USA Toyama ryu Headquarters), as well as USA Nakamura ryu Honbu upon my departure to the United States. (A copy of the scrolls from Nakamura sensei are reprinted in the book NAKED BLADE)

At the time, I was a fifth dan in battodo, and that was when dan ranking requirements were very strict. It was an honor for me to receive such a high rank, and I was the first student in my age group to do so. I believe that the decision to come to America and my numerous awards gave Nakamura sensei the impetus to give me that dan.

Subsequently, Nakamura sensei received a 10th dan ranking in battodo from the Kokusai Budoin and shortly after that ranks were more freely distributed. Although battodo was based upon Toyama ryu, Nakamura sensei felt the need to spread battodo by accepting practitioners from other arts, regardless of their lack of knowledge in the art and techniques of Toyama ryu. I know of one University instructor in karate who was awarded a 9th dan honorary ranking, as well as students receiving 3rd dan ranks within their first year of study. Promotions were given to branch instructors solely to further battodo teachings, with many martial artists receiving equivalent dan ratings overnight, or after attending a seminar. This frivolous awarding of ranks destroys the whole value of the dan/kyu system, especially when those receiving the rating don't understand that the rank is only honorary.

Toyama ryu [as passed through the Nakamura line] has only eight kata and six kumitachi in its curriculum, many practitioners scoffed at the simplicity of the movements and doubted its combat efficiency. Furthermore, the main emphasis became test cutting tatami omote and swordsmiths deviated from traditional Japanese swords and began to create specially designed blades that were thin and wide to better cut through these style targets. These swords would chip or break if someone attempted to cut through bamboo with them.

Show Biz

After being an uchideshi for seven years, I left the Yoshinkan to join Wakakoma. I had met Mr. Hayashi through his affiliation with Nakamura sensei, as one of his directors. He and I had an excellent rapport and he had often asked my opinion on martial arts matters. As the chief Action Coordinator for Wakakoma Productions, Mr. Hayashi offered me a position to join him. I was to be Shihan of Martial Arts in the Wakakoma dojo. This gave me an opportunity to learn the profession of a tateshi (action coordinator), as well as pursue my own sword study.

I was the aikido specialist, and soon after I joined I commented that being Mr. Hayashi was our instructor, that he should be addressed as "Hayashi sensei". From then on, he was always referred to as Hayashi sensei. The studio became traditional and more serious, although the movie action was always fun. It was a whole new world for me, work seemed more like play; swimming, diving and horseback riding.

Although I would never go against my superior, I did do one thing that may be construed as rebellious. I wanted Hayashi sensei to stop smoking and I told him that I was prepared to quit Wakakoma if he did not. To my surprise, he readily agreed and quit smoking, which pleased me greatly.

Hayashi sensei was a renowned action coordinator and worked for all the major TV series for the NHK network. He wanted to put more martial arts into movie action and make it more realistic. I feel very fortunate to have worked with him, and gained an incredible amount of experience through my association with Wakakoma.

Establishing Shinkendo - Japanese Swordsmanship

Although I was in America at the time, I still heard of the discontentment with the battodo organization in Japan. Battodo was very important to me, and I was disappointed that so few truly knew the history and objective of its teachings. I saw the changes in the organization and I could not change their philosophy; and it would have been inappropriate to do so. Although I respected Nakamura sensei for following his belief that a sword was an object to be used, and not a decoration, I felt there were others with superior sword technique and it was time for me to move on. Therefore, I elected to follow the rule of "shu ha ri", and separate from the organization. What this means is that I continue to have the USA headquarters for both battodo and Toyama ryu, but we function independently from the Japanese organization.

I remembered as a child, wandering around in the mountains where I grew up. My 'toys' were things like hatchets and pick-axes! Later, I started my martial arts career and pursued different styles. I learned the speed of kendo, the paired kata of Yagyu shinkage ryu and Kashima shin ryu, the power of Jigen ryu, the accuracy of Ioriken battojutsu, the body movements of Ryukyu Kobudo, the balance of aikido, and the experiences of the battodo tournaments. Every art has it's good points, and I incorporated them into shinkendo. Gaiden refers to a technique from another school. I continue to teach Toyama ryu in my shinkendo organization; however, it is in the form of Shinkendo Gaiden Toyama ryu.

"Ju yoku go o seishi. Go yoku ju o tatsu. Hi ke ba ose, ose ba maware." Soft controls hard. Hard cuts soft. If pulled, push. If pushed, turn. These are the elements I looked to while developing shinkendo, gathering the best in all the styles I had studied and building on the basic "go, ju, ryu, ki, rei" concept, to create a practical technique that was refined and patterned after the feudal samurai.

The dan/kyu system is not used in shinkendo, but ranks are based upon an older system that was used during the samurai era. Practitioners are divided into three groups; seito, deshi and kyakubun. No honorary ranks are awarded or allowed for under this system.

Shinkendo's headquarters, or honbu, is located in Los Angeles, California. Slowly and deliberately, a precise sword style is spreading throughout the world by shinkendo instructors and practitoners.

I would like people to learn practical techniques, safety, correct cutting angles, proper gripping of the sword, and methods of stopping the sword effectively. In addition, there is a need to master basic suburi, kata, battoho and tachiuchi (sparring), footwork and body movement. Test cutting alone is not the ultimate goal. A full and complete integration of sword and practice and its concepts should be achieved before one touches a real sword. I have always been very concerned about the numerous incidents of injuries relating to sword demonstrations. Accidents such as cut hands or sliced fingers, and stabbing wounds inflicted by one's self should not be a part of normal swordsmanship practice, or considered some kind of "badge of shugyo", but understood to be the result of inadequate instruction or practice. I recently heard of an exhibition where a sword man used another person in the performance (cutting radishes against his neck), and the man's assistant was grievously injured. This kind of wanton and reckless display shows a total lack of respect for the art of sword, and belongs in a circus performance or sideshow. Swordsmanship is an art form, and should be treated with the utmost dignity and respect.

Techniques take time to develop and mature, and one of the main qualities I look for in students is their spirit of jinsei shinkendo (life is shinkendo/shinkendo is life). In other words, apply the values and teachings found in shinkendo training to other areas of your life, as well as use life-experiences to better understand shinkendo. Those students who strive to improve themselves through self reflection and are diligent in their pursuit of goals - they are the ones who I would like to spread the art.

The precepts that I modeled shinkendo after are universal. Shinkendo offers people an opportunity to network in a worldwide theatre with others studying sword. It is the opportunity to practice a strong method, to lead a serious life and train your mind and spirit, while respecting nature and promoting peace.

Shinkendo has a number of meanings depending on the calligraphy, or kanji, used to depict the various characters. Shinken is what a real Japanese sword is called; however, shin can also mean true or serious, as in your pursuit of life and training (therefore, the term "shinkendo" can also be interpreted as "the way of living your life seriously and fully".); shin can also mean mind and spirit, as the art affords you a way to forge both. Shin can mean god, in that we should respect our world and nature, and espouse world peace. Shinkendo does not have to stop at the door of the dojo, but can be thought of as a path to follow, and a strategy of mind to apply in your life and its day to day activities. That is how this art came about. I created the International Shinkendo Federation to promote those ideals, because the truth begets the truth...

Soke Obata Toshishiro, October 1996.

Please direct questions and comments to:

![]()